Anatomy of the Breast

As with all surgical procedures, understanding the anatomy is crucial prior to performing an operative procedure. Comprehension of breast anatomy enhances the surgeon's ability to perform surgery safely and effectively. For information on various breast surgery procedures, please see the Breast section of eMedicine's Plastic Surgery journal.

Vascular Anatomy

The blood supply to the breast skin depends on the subdermal plexus, which is in communication with underlying deeper vessels supplying the breast parenchyma. The blood supply is derived from (1) the internal mammary perforators (most notably the second to fifth perforators), (2) the thoracoacromial artery, (3) the vessels to serratus anterior, (4) the lateral thoracic artery, and (5) the terminal branches of the third to eighth intercostal perforators. The superomedial perforator supply from the internal mammary vessels is particularly robust and accounts for some 60% of the total breast blood supply. This rich blood supply allows for various reduction techniques, ensuring the viability of the skin flaps after surgery.

Innervation of the Breast

Sensory innervation of the breast is dermatomal in nature. It is mainly derived from the anterolateral and anteromedial branches of thoracic intercostal nerves T3-T5. Supraclavicular nerves from the lower fibers of the cervical plexus also provide innervation to the upper and lateral portions of the breast. Researchers believe sensation to the nipple derives largely from the lateral cutaneous branch of T4.

Breast Parenchyma and Support Structures

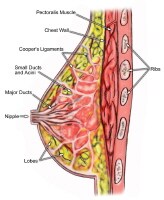

The breast is made up of both fatty tissue and glandular milk-producing tissues. The ratio of fatty tissue to glandular tissue varies among individuals. In addition, with the onset of menopause (ie, decrease in estrogen levels), the relative amount of fatty tissue increases as the glandular tissue diminishes.

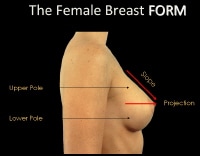

The base of the breast overlies the pectoralis major muscle between the second and sixth ribs in the nonptotic state. The gland is anchored to the pectoralis major fascia by the suspensory ligaments first described by Astley Cooper in 1840. These ligaments run throughout the breast tissue parenchyma from the deep fascia beneath the breast and attach to the dermis of the skin. Since they are not taut, they allow for the natural motion of the breast. These ligaments relax with age and time, eventually resulting in breast ptosis. The lower pole of the breast is fuller than the upper pole. The tail of Spence extends obliquely up into the medial wall of the axilla.[1]

The breast overlies the pectoralis major muscle as well as the uppermost portion of the rectus abdominis muscle inferomedially. The nipple should lie above the inframammary crease and is usually level with the fourth rib and just lateral to the midclavicular line. The average nipple – to – sternal notch measurement in a youthful, well-developed breast is 21-22 cm; an equilateral triangle formed between the nipples and sternal notch measures an average of 21 cm per side.

The base of the breast overlies the pectoralis major muscle between the second and sixth ribs in the nonptotic state. The gland is anchored to the pectoralis major fascia by the suspensory ligaments first described by Astley Cooper in 1840. These ligaments run throughout the breast tissue parenchyma from the deep fascia beneath the breast and attach to the dermis of the skin. Since they are not taut, they allow for the natural motion of the breast. These ligaments relax with age and time, eventually resulting in breast ptosis. The lower pole of the breast is fuller than the upper pole. The tail of Spence extends obliquely up into the medial wall of the axilla.[1]

The breast overlies the pectoralis major muscle as well as the uppermost portion of the rectus abdominis muscle inferomedially. The nipple should lie above the inframammary crease and is usually level with the fourth rib and just lateral to the midclavicular line. The average nipple – to – sternal notch measurement in a youthful, well-developed breast is 21-22 cm; an equilateral triangle formed between the nipples and sternal notch measures an average of 21 cm per side.

Musculature Related to the Breast

The breast lies over the musculature that encases the chest wall. The muscles involved include the pectoralis major, serratus anterior, external oblique, and rectus abdominus fascia. The blood supply that provides circulation to these muscles then perforates through to the breast parenchyma, thus also supplying blood to the breast. By maintaining continuity with the underlying musculature, the breast tissue remains richly perfused, thus preventing complications arising from aesthetic or reconstructive surgery that requires the placement of a breast implant. (For more information, see the Breast section of eMedicine's Plastic Surgery journal.)

Pectoralis major

The pectoralis major muscle is a broad muscle that extends from its origin on the medial clavicle and lateral sternum to its insertion on the humerus. The thoracoacromial artery provides its major blood supply, while the intercostal perforators arising from the internal mammary artery provide a segmental blood supply. The medial and lateral anterior thoracic nerves provide innervation for the muscle, entering posteriorly and laterally. The action of the pectoralis major is to flex, adduct, and rotate the arm medially.

The pectoralis major is extremely important in both aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery, since it provides muscle coverage for the breast implant. In reconstructive surgery, the pectoralis major muscle covers the implant, providing a decreased risk of exposure of the implant since the skin and underlying subcutaneous tissues are often thin following mastectomy. The muscle also provides additional tissue between implant and skin, thus decreasing palpability of the implant. Often, placement of the implant beneath the muscle causes it to be noticeable when the pectoralis is contracted. In these instances, it may be helpful to release the pectoralis muscle from its inferior and medial attachments to decrease the incidence of noticeable contractions. In addition, with inferior release of the pectoralis muscle, lower positioning of the implant can be achieved, resulting in a more aesthetically pleasing appearance.

Serratus anterior

The serratus anterior muscle is a broad muscle that runs along the anterolateral chest wall. Its origin is the outer surface of the upper borders of the first through eighth ribs, and its insertion is on the deep surface of the scapula. Its vascular supply is derived equally from the lateral thoracic artery and branches from the thoracodorsal artery. The long thoracic nerve serves to innervate the serratus anterior, which acts to rotate the scapula, raising the point of the shoulder and drawing the scapula forward toward the body. Transection of the long thoracic nerve is carefully avoided during an axillary lymph node dissection, since its loss results in "winging" as the scapula is released from the chest wall and moves upward and outward.

Because the serratus anterior underlies the lateral aspect of the breast, in aesthetic surgery, blunt elevation of the pectoralis major laterally inadvertently elevates a small portion of the serratus muscle. To completely cover the implant with muscle in reconstructive surgery, often the serratus anterior must be elevated sharply to obtain a sufficient muscle layer to provide coverage.

Rectus abdominus

The rectus abdominus muscle demarcates the inferior border of the breast. It is an elongated muscle that runs from its origin at the crest of the pubis and interpubic ligament to its insertion at the xiphoid process and cartilages of the fifth through seventh ribs. It acts to compress the abdomen and flex the spine. The 7th through 12th intercostal nerves provide sensation to overlying skin and innervate the muscle. Vascularity of the muscle is maintained through a network between the superior and inferior deep epigastric arteries.

When placing an implant for breast reconstruction, in attempting to achieve complete coverage with muscle, the rectus fascia must often be elevated to place the implant sufficiently caudal. This dense thick fascia is often intimately adherent to the ribs below it. Once it is elevated and released, proper positioning and expansion of the implant can proceed.

External oblique

The external oblique muscle is a broad muscle that runs along the anterolateral abdomen and chest wall. Its origin is from the lower 8 ribs, and its insertion is along the anterior half of the iliac crest and the aponeurosis of the linea alba from the xiphoid to the pubis. It acts to compress the abdomen, flex and laterally rotate the spine, and depress the ribs. The 7th through 12th intercostal nerves serve to innervate the external oblique. A segmental blood supply is maintained through the inferior 8 posterior intercostal arteries.

The external oblique muscle abuts the breast on the inferior lateral aspect. Elevated along with the rectus abdominus fascia to provide inferior coverage of the breast implant during reconstructive surgery, its fascia, like the fascia of the rectus abdominus muscle, must be released adequately to provide for proper placement and expansion of the implant. In aesthetic surgery, placement of the implant inferiorly is usually not below these fascial attachments. If the implant is placed behind the fascia, the implant often "rides too high" and may result in a "double bubble" effect, wherein the breast parenchyma slides over and off the implant.

Conclusion

Breast shape varies among patients, but knowing and understanding the anatomy of the breast ensures safe surgical planning. When the breasts are carefully examined, significant asymmetries are revealed in most patients. Any preexisting asymmetries, spinal curvature, or chest wall deformities must be recognized and demonstrated to the patient, as these may be difficult to correct and can become noticeable in the postoperative period. Preoperative photographs with multiple views are obtained on all patients and maintained as part of the office record.

Pectoralis major

The pectoralis major muscle is a broad muscle that extends from its origin on the medial clavicle and lateral sternum to its insertion on the humerus. The thoracoacromial artery provides its major blood supply, while the intercostal perforators arising from the internal mammary artery provide a segmental blood supply. The medial and lateral anterior thoracic nerves provide innervation for the muscle, entering posteriorly and laterally. The action of the pectoralis major is to flex, adduct, and rotate the arm medially.

The pectoralis major is extremely important in both aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery, since it provides muscle coverage for the breast implant. In reconstructive surgery, the pectoralis major muscle covers the implant, providing a decreased risk of exposure of the implant since the skin and underlying subcutaneous tissues are often thin following mastectomy. The muscle also provides additional tissue between implant and skin, thus decreasing palpability of the implant. Often, placement of the implant beneath the muscle causes it to be noticeable when the pectoralis is contracted. In these instances, it may be helpful to release the pectoralis muscle from its inferior and medial attachments to decrease the incidence of noticeable contractions. In addition, with inferior release of the pectoralis muscle, lower positioning of the implant can be achieved, resulting in a more aesthetically pleasing appearance.

Serratus anterior

The serratus anterior muscle is a broad muscle that runs along the anterolateral chest wall. Its origin is the outer surface of the upper borders of the first through eighth ribs, and its insertion is on the deep surface of the scapula. Its vascular supply is derived equally from the lateral thoracic artery and branches from the thoracodorsal artery. The long thoracic nerve serves to innervate the serratus anterior, which acts to rotate the scapula, raising the point of the shoulder and drawing the scapula forward toward the body. Transection of the long thoracic nerve is carefully avoided during an axillary lymph node dissection, since its loss results in "winging" as the scapula is released from the chest wall and moves upward and outward.

Because the serratus anterior underlies the lateral aspect of the breast, in aesthetic surgery, blunt elevation of the pectoralis major laterally inadvertently elevates a small portion of the serratus muscle. To completely cover the implant with muscle in reconstructive surgery, often the serratus anterior must be elevated sharply to obtain a sufficient muscle layer to provide coverage.

Rectus abdominus

The rectus abdominus muscle demarcates the inferior border of the breast. It is an elongated muscle that runs from its origin at the crest of the pubis and interpubic ligament to its insertion at the xiphoid process and cartilages of the fifth through seventh ribs. It acts to compress the abdomen and flex the spine. The 7th through 12th intercostal nerves provide sensation to overlying skin and innervate the muscle. Vascularity of the muscle is maintained through a network between the superior and inferior deep epigastric arteries.

When placing an implant for breast reconstruction, in attempting to achieve complete coverage with muscle, the rectus fascia must often be elevated to place the implant sufficiently caudal. This dense thick fascia is often intimately adherent to the ribs below it. Once it is elevated and released, proper positioning and expansion of the implant can proceed.

External oblique

The external oblique muscle is a broad muscle that runs along the anterolateral abdomen and chest wall. Its origin is from the lower 8 ribs, and its insertion is along the anterior half of the iliac crest and the aponeurosis of the linea alba from the xiphoid to the pubis. It acts to compress the abdomen, flex and laterally rotate the spine, and depress the ribs. The 7th through 12th intercostal nerves serve to innervate the external oblique. A segmental blood supply is maintained through the inferior 8 posterior intercostal arteries.

The external oblique muscle abuts the breast on the inferior lateral aspect. Elevated along with the rectus abdominus fascia to provide inferior coverage of the breast implant during reconstructive surgery, its fascia, like the fascia of the rectus abdominus muscle, must be released adequately to provide for proper placement and expansion of the implant. In aesthetic surgery, placement of the implant inferiorly is usually not below these fascial attachments. If the implant is placed behind the fascia, the implant often "rides too high" and may result in a "double bubble" effect, wherein the breast parenchyma slides over and off the implant.

Conclusion

Breast shape varies among patients, but knowing and understanding the anatomy of the breast ensures safe surgical planning. When the breasts are carefully examined, significant asymmetries are revealed in most patients. Any preexisting asymmetries, spinal curvature, or chest wall deformities must be recognized and demonstrated to the patient, as these may be difficult to correct and can become noticeable in the postoperative period. Preoperative photographs with multiple views are obtained on all patients and maintained as part of the office record.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق