Overview

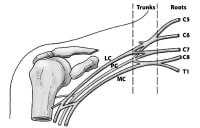

The brachial plexus (plexus brachialis) is a somatic nerve plexus formed by intercommunications among the ventral rami (roots) of the lower 4 cervical nerves (C5-C8) and the first thoracic nerve (T1).

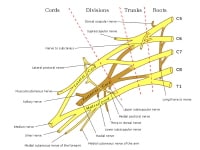

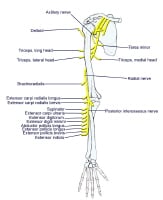

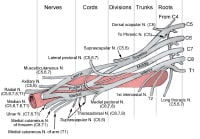

The plexus is responsible for the motor innervation to all of the muscles of the upper extremity with the exception of the trapezius and levator scapula. The image below depicts the brachial plexus (BP).

|

| The basic anatomical relationships of the brachial plexus (BP). The BP is subdivided into roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches. LC stands for lateral cord, PC stands for the posterior cord, and MC stands for the medial cord | | | | | | | | | | |

The BP supplies all of the cutaneous innervation of the upper limb, except for the area of the axilla (which is supplied by the supraclavicular nerve) and the dorsal scapula area, which is supplied by cutaneous branches of the dorsal rami.

The BP communicates with the sympathetic trunk via gray rami communicantes, which join the roots of the plexus. They are derived from the middle and inferior cervical sympathetic ganglia and the first thoracic sympathetic ganglion.

Gross Anatomy

Brachial plexus architecture

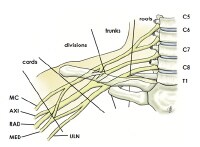

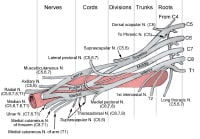

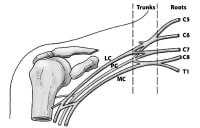

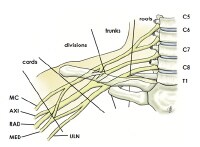

The brachial plexus (BP) is subdivided into roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches. Several mnemonics can be used to remember this architecture (eg, Really Tired Drink Coffee Black). Typically, the brachial plexus is composed of 5 roots, 3 trunks, 6 divisions, 3 cords, and terminal branches, as seen in the image below

|

| Brachial plexus with terminal branches labeled. MC is musculocutaneous (nerve), AXI is axillary, RAD is radial, MED is median, and ULN is ulnar. | |

Roots

The ventral rami of spinal nerves C5 to T1 are referred to as the "roots" of the plexus. The typical spinal nerve root results from the confluence of the ventral nerve rootlets originating in the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord and the dorsal nerve rootlets that join the spinal ganglion in the region of the intervertebral foramen.

The roots emerge from the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae immediately posterior to the vertebral artery, which travels in a cephalocaudad direction through the transverse foramina. Each transverse process consists of a posterior and anterior tubercle, which meet laterally to form a costotransverse bar. The transverse foramen lies medial to the costotransverse bar and between the posterior and anterior tubercles. The spinal nerves that form the brachial plexus run in an inferior and anterior direction within the sulci formed by these structures.

Trunks

Shortly after emerging from the intervertebral foramina, the 5 roots (C5-T1) unite to form 3 trunks. The trunks of the BP pass between the anterior and middle scalene muscles.

The ventral rami of C5 and C6 unite to form the upper trunk. The suprascapular nerve and the nerve to the subclavius arise from the upper trunk. The suprascapular nerve contributes sensory fibers to the shoulder joint and provides motor innervation to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.

The ventral ramus of C7 continues as the middle trunk. The ventral rami of C8 and T1 unite to form the lower trunk .

Divisions

Each trunk splits into an anterior division and a posterior division. These separate the innervation of the ventral and dorsal aspect of the upper limb. The anterior divisions usually supply flexor muscles. The posterior divisions usually supply extensor muscles.

Cords

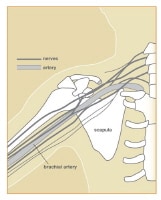

The cords are referred to as the lateral, posterior, and medial cord, according to their relationship with the axillary artery, as seen in the image below.

The cords pass over the first rib close to the dome of the lung and continue under the clavicle immediately posterior to the subclavian artery.

The anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks unite to form the lateral cord, which is the origin of the lateral pectoral nerve (C5, C6, C7).

The anterior division of the lower trunk forms the medial cord, which gives off the medial pectoral nerve (C8, T1), the medial brachial cutaneous nerve (T1), and the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (C8, T1).

The posterior divisions from each of the 3 trunks unite to form the posterior cord.

The upper and lower subscapular nerves (C7, C8 and C5, C6, respectively) leave the posterior cord and descend behind the axillary artery to supply the subscapularis and teres major muscles. The thoracodorsal nerve to the latissimus dorsi (also known as the middle subscapular nerve, C6, C7, C8) also arises from the posterior cord, as seen in the image below.

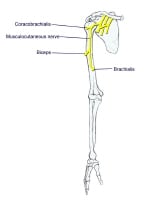

Musculocutaneous nerve branch

These are mixed nerves containing both sensory and motor axons (as seen in the image below). The musculocutaneous nerve is derived from the lateral cord. The musculocutaneous nerve leaves the BP sheath high in the axilla at the level of the lower border of the teres major muscle and passes into the coracobrachialis muscle. It innervates the muscles in the flexor compartment of the arm. It carries sensation from the lateral (radial) side of the forearm.

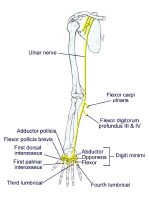

Ulnar nerve branch

The ulnar nerve is derived from the medial cord. Motor innervation is mainly to intrinsic muscles of the hand (as seen in the image below). Sensory innervation is from the medial (ulnar) 1.5 digits (little finger and one-half of the ring finger).

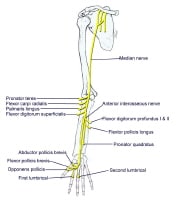

Median nerve branch

The median nerve is derived from both the lateral and medial cords. Motor innervation is to most flexor muscles in the forearm and intrinsic muscles of the thumb (thenar muscles), as seen in the image below. Sensory innervation is to the lateral (radial) 3.5 digits (thumb, index, middle, and half of the ring finger).

Axillary nerve branch

The axillary nerve is derived from the posterior cord. The axillary nerve leaves the BP at the lower border of the subscapularis muscle and continues along the inferior and posterior surface of the axillary artery as the radial nerve. The axillary nerve serves as motor innervation to the deltoid and teres minor muscles, as seen in the image below. These act at the glenohumeral joint. Sensory innervation is from the skin just below the point of the shoulder. The axillary nerve continues as the superior lateral brachial cutaneous nerve of the arm.

Radial nerve branch

The radial nerve is also derived from the posterior cord. The radial nerve continues along the posterior and inferior surface of the axillary artery. The radial nerve innervates the extensor muscles of the elbow, wrist, and fingers, as seen in the image above. Sensory innervation is from the skin on the dorsum of the hand on the radial side.

Terminal Branches

Five "terminal" branches and numerous other "pre-terminal" or "collateral" branches leave the plexus at various points along its length.

Dorsal scapular nerve

The dorsal scapular nerve is derived from the C5 root just after its exit from the intervertebral foramen. It serves as the motor nerve to the rhomboids major and minor muscles

Long thoracic nerve

The long thoracic nerve is derived from C5, C6, and C7 roots immediately after their emergence from the intervertebral foramina. The long thoracic nerve crosses the first rib and then descends through the axilla behind the major branches of the plexus. It innervates the serratus anterior muscle.

Phrenic nerve

The phrenic nerve arises from C3, C4, and C5 root levels, chiefly from the C4 nerve root. It crosses the anterior scalene from lateral to medial and extends into the thorax between the subclavian vein and artery.

Subclavius muscle nerve

The nerve to the subclavius muscle is a small filament, which arises from the upper trunk. It descends to the subclavius muscle in front of the subclavian artery and the lower trunk of the plexus.

Suprascapular nerve

The suprascapular nerve arises from the upper trunk formed by the union of the fifth and sixth cervical nerves. It innervates the supraspinatus muscles and infraspinatus muscles. It runs laterally beneath the trapezius and the omohyoideus and enters the supraspinatus fossa through the suprascapular notch, below the superior transverse scapular ligament; it then passes beneath the supraspinatus and curves around the lateral border of the spine of the scapula to the infraspinatus fossa.

Lateral pectoral nerve

The lateral pectoral nerve arises from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus, from the fifth, sixth, and seventh cervical nerves. It passes across the axillary artery and vein, pierces the coracoclavicular fascia, and is distributed to the deep surface of the pectoralis major. It sends a filament to join the medial anterior thoracic and forms with it a loop in front of the first part of the axillary artery. This nerve innervates the clavicular head of the pectoralis major muscle.

Medial pectoral nerve

The medial pectoral nerve arises from the medial cord from the eighth cervical and first thoracic nerve. It passes behind the first part of the axillary artery, curves forward between the axillary artery and vein, and unites in front of the artery with a filament from the lateral nerve. It then enters the deep surface of the pectoralis minor, where it divides into a number of branches, which supply the muscle. Several branches of the medial pectoral nerve pierce the muscle and end in the pectoralis major, which supply the muscle.

The medial and lateral pectoral nerve often join together to act as a single nerve innervating both the pectoralis major and minor muscles.

Medial brachial cutaneous nerve

The medial brachial cutaneous nerve is the smallest branch of the brachial plexus and, arising from the medial cord, receives its fibers from the eighth cervical and first thoracic nerves. It passes through the axilla, at first lying behind and then medial to the axillary vein, and communicates with the intercostobrachial nerve. It descends along the medial side of the brachial artery to the middle of the arm, where it pierces the deep fascia, and is distributed to the skin of the back of the lower third of the arm, extending as far as the elbow, where some filaments are lost in the skin in front of the medial epicondyle, and others over the olecranon. It communicates with the ulnar branch of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. It carries sensation from the lower medial portion of the arm.

Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve

The medial antebrachial cutaneous arises from the medial cord of the brachial plexus. It derives its fibers from the eighth cervical and first thoracic nerves, and at its commencement is medial to the axillary artery. It gives off, near the axilla, a filament, which pierces the fascia and supplies the integument covering the biceps brachii, nearly as far as the elbow. The nerve then runs down the ulnar side of the arm medial to the brachial artery, pierces the deep fascia with the basilic vein, about the middle of the arm, and divides into a volar and an ulnar branch.

Microscopic Anatomy

Blood supply of the brachial plexus

The blood supply of the brachial plexus is based largely on the subclavian (which becomes the axillary) artery and its branches, and variations exist. Generally, the vessels involved are the vertebral, the ascending and deep cervical, and the superior intercostal arteries. The cord and rootlets of the cervical nerves are supplied by the anterior and posterior spinal branches of the vertebral artery. The trunks of the plexus are supplied by muscular branches of the ascending and deep cervical arteries and superior intercostals, and occasionally from the subclavian itself.

Natural Variants

Many variant forms of the brachial plexus exist, with none representing most patients. Kerr catalogued 29 forms of the brachial plexus among some 175 cadaver specimens dissected between 1895 and 1910.[2] In the early part of the last century, one author described a total of 38 variations of the plexus. Up to 53.5% of plexuses in cadaver studies possess significant anatomic variation from the "classic" description of the brachial plexus. A study published in September 2003 found variants in 107 of 200 fetuses examined. The authors pointed out that morphological variations were more common in female fetuses and right sides.[3]

Prefixed brachial plexus (cephalic or high)

This occurs when the C4 ventral ramus contributes to the brachial plexus. Contributions to the plexus usually come from the C4-C8.

Postfixed brachial plexus (caudal or low)

This occurs when the T2 ventral ramus contributes to the brachial plexus. Contributions to the plexus usually come from C6-T2.

Other Considerations

Lesions of the Brachial Plexus

Knowledge of the muscles innervated by branches of the brachial plexus and the actions of these muscles and areas of anesthesia and/or paraesthesia allows the physician to determine the localization of a given lesion.

Brachial plexus injuries have numerous causes, such as labor and delivery. A plexus injury at birth is likely caused by a stretch or tear of the child's brachial plexus during the delivery process. The abducted arm of the infant can get pinned against the child's head. This injury results in incomplete sensory and/or motor function of the injured nerve. Traumatic brachial plexus injuries may occur due to motor vehicle accidents, bike accidents, ATV accidents, or sports.

Nerve injuries vary in severity from a mild stretch to the nerve root tearing away from the spinal cord.

Avulsion

The nerve is torn away from its attachment at the spinal cord; this is the most severe type of injury.

Rupture

The nerve is torn, but not at the spinal cord attachment.

Neuroma

Scar tissue has grown around the injury site, putting pressure on the injured nerve and preventing the nerve from sending signals to the muscles.

Neurapraxia

The nerve has been stretched and damaged but not torn.

Diagnoses Related to Brachial Plexus Injuries

Diagnoses related to brachial plexus injuries include Erb palsy, Klumpke palsy, thoracic outlet syndrome, Burner syndrome, and Parsonage-Turner syndrome.

Erb palsy

This condition involves the upper root nerves of C5, C6.

The patient often presents with the arm extended and wrist fully flexed (waiter's tip).

Motor deficits are loss of abduction, flexion, and rotation at the shoulder (axillary, suprascapular, upper, and lower subscapular nerve); weak shoulder extension; and weak elbow flexion and supination of the radioulnar joint (musculocutaneous and radial nerve).

The patient is susceptible to shoulder dislocation due to loss of rotator cuff muscles .

Sensory deficits are to the posterior and lateral aspect of arm (axillary nerve ), radial side of the forearm (musculocutaneous nerve), and thumb and first finger (superficial branch of radial nerve; digital branches of the median nerve ).

Klumpke palsy

This condition involves the lower root nerves of C8 and T1.

This is caused by a rare injury of the lower brachial plexus, usually following breech delivery.

Motor deficits are opposite the thumb (thenar branch of the median nerve), loss of adduction of the thumb (ulnar nerve), loss of abduction and adduction of metatarsophalangeal joints; flexion at the metatarsophalangeal and extension of the interphalangeal joints (deep branch of ulnar and median), and weak flexion of proximal interphalangeal joints and distal interphalangeal joints (ulnar and median nerve).

Sensory deficit is to the ulnar side of the forearm, hand, and ulnar one and a half digits (ulnar and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve).

Thoracic outlet syndrome

This condition is caused by compression of the neurovascular structures (subclavian vessels, brachial plexus, cervical ganglia, and vertebral artery) in the cervicoaxillary region. It may be congenital or acquired.

Bony causes include the following: long transverse process of the seventh cervical vertebra, cervical rib, anomalous first rib, clavicle fracture, and first rib fracture.

Soft tissue causes include the following: congenital bands, poor posture, mass lesions, cervical strain, hypertrophy, and/or injury of the anterior and middle scalene muscles or the pectoralis minor muscle.

Burner syndrome

This condition is thought to be related to brachial plexus stretch and/or nerve root compression. It generally involves the upper trunk of the brachial plexus, particularly C5-C6.

This condition is usually a result of traction injury with axial distraction or downward force on the shoulder combined with lateral bend of the neck away from the shoulder.

Brachial plexus stretch injuries are found in young athletes, with neck pain being less common.

Nerve root compression is found in older athletes (college), generally associated with cervical disc disease or cervical stenosis. Neck pain is more common.

Parsonage-Turner syndrome (brachial neuritis)

This condition is generally associated with a viral prodrome, immunizations, and significant pain.

Acute excruciating unilateral shoulder pain is present, followed by flaccid paralysis of shoulder and parascapular muscles several days later.

This condition varies greatly in manifestation and nerve involvement. Due to the extreme pain involved, patients usually present acutely. Often, the affected arm is supported by the uninvolved arm and is held in adduction and internal rotation.

The patient may have atrophy of the affected muscles.

Pain may occur with palpation and active and passive range of motion.

Reflexes may be reduced/absent, depending on the nerves involved.

Sensory loss is usually not prominent, although it may be detectable.

This condition may cause scapular winging.